416

TARANTULA—TARASCON

construction of the bridge over the channel to the N.W. of the

town, and of the aqueduct which passes over it. The town was taken by Robert Guiscard in 1063. His son Bohemond became prince of the Terra d'Otranto, with his capital here. After his death Roger II. of Sicily gave it to his son William the Bad. The emperor Frederick II. erected a castle (Rocca Imperiale) at the highest point of the city. In 1301 Philip, the son of Charles II. of Anjou, became prince of Taranto. The castle dates from the Aragonese period. The tarantula (see below), inhabits the neighbourhood of Taranto. The wild dance, called tarantella, was supposed, by causing perspiration, to drive out the poison of the bite. (T. As.)

TARANTULA, strictly speaking, a large spider (Lycosa

tarantula), which takes its name from the town of Taranto

(Tarentum) in Apulia, near which it occurs and where it was

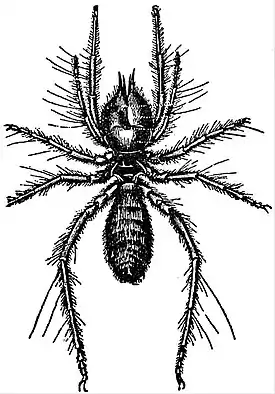

Galeodes lucasii, an Arachnid of the order

Solifugae, commonly but wrongly called

tarantula in Egypt.

formerly believed to

be the cause of the

malady known as

“tarantism.” This

spider belongs to the

family Lycosidae, and

has numerous allies,

equalling or surpassing

it in size, in various

parts of the world,

the genus Lycosa being

almost cosmopolitan

in distribution. The

tarantula, like all its

allies, spins no web as

a snare but catches

its prey by activity

and speed of foot. It

lives on dry,

well-drained ground, and

digs a deep burrow

lined with silk to

prevent the infall of

loose particles of soil.

In the winter it

covers the orifice of

this burrow with a layer of silk, and lies dormant underground

until the return of spring. It also uses the burrow as a safe

retreat during moulting and guards its cocoon and young in

its depths. It lives for several years. The male is approximately

the same size as the female, but in neither sex does

the length of the body surpass three-quarters of an inch. Like

all spiders, the tarantula possesses poison glands in its jaws,

but there is not a particle of trustworthy evidence that the

secretion of these glands is more virulent than that of other

spiders of the same size, and the medieval belief that the bite

of the spider gave rise to tarantism has long been abandoned.

According to traditional accounts the first symptom of this

disorder was usually a state of depression and lethargy. From

this the sufferer could only be roused by music, which excited

an overpowering desire to dance until the performer fell to

the ground bathed in profuse perspiration, when the cure, at

all events for the time, was supposed to be effected. This

mania attacked both men and women, young and old alike,

women being more susceptible than men. It was also considered

to be highly infectious and to spread rapidly from

person to person until whole areas were affected. The name

tarantella, in use at the present time, applies both to a dance

still in vogue in Southern Italy and also to musical pieces

resembling in their stimulating measures those that were

necessary to rouse to activity the sufferer from tarantism in

the middle ages. In recent times the term tarantula has been

applied indiscriminately to many different kinds of large spiders

in no way related to Lycosa tarantula; and to at least one

Arachnid belonging to a distinct order. In most parts of

America, for example, where English is spoken, species of

Aviculariidae, or “Bird-eating” spiders of various genera, are

invariably called tarantulas. These spiders are very much

larger and more venomous than the largest of the Lycosidae,

and in the Southern states of North America the species of

wasps that destroy them have been called tarantula hawks.

In Queensland one of the largest local spiders, known as

Holconia immanis, a member of the family Clubionidae, bears

the name tarantula; and in Egypt it was a common practice

of the British soldiers to put together scorpions and tarantulas,

the latter in this instance being specimens of the large and

formidable desert-haunting Arachnid, Galeodes lucasii, a member

of the order Solifugae. Similarly in South Africa species of

the genus Solpuga, another member of the Solifugae, were employed

for the same purpose under the name tarantula. Finally

the name Tarantula, in a scientific and systematic sense, was

first given by Fabricius to a Ceylonese species of amblypygous

Pedipalpi, still sometimes quoted as Phrynus lunatus. (R. I. P.)

Galeodes lucasii, an Arachnid of the order

Solifugae, commonly but wrongly called

tarantula in Egypt.

formerly believed to

be the cause of the

malady known as

“tarantism.” This

spider belongs to the

family Lycosidae, and

has numerous allies,

equalling or surpassing

it in size, in various

parts of the world,

the genus Lycosa being

almost cosmopolitan

in distribution. The

tarantula, like all its

allies, spins no web as

a snare but catches

its prey by activity

and speed of foot. It

lives on dry,

well-drained ground, and

digs a deep burrow

lined with silk to

prevent the infall of

loose particles of soil.

In the winter it

covers the orifice of

this burrow with a layer of silk, and lies dormant underground

until the return of spring. It also uses the burrow as a safe

retreat during moulting and guards its cocoon and young in

its depths. It lives for several years. The male is approximately

the same size as the female, but in neither sex does

the length of the body surpass three-quarters of an inch. Like

all spiders, the tarantula possesses poison glands in its jaws,

but there is not a particle of trustworthy evidence that the

secretion of these glands is more virulent than that of other

spiders of the same size, and the medieval belief that the bite

of the spider gave rise to tarantism has long been abandoned.

According to traditional accounts the first symptom of this

disorder was usually a state of depression and lethargy. From

this the sufferer could only be roused by music, which excited

an overpowering desire to dance until the performer fell to

the ground bathed in profuse perspiration, when the cure, at

all events for the time, was supposed to be effected. This

mania attacked both men and women, young and old alike,

women being more susceptible than men. It was also considered

to be highly infectious and to spread rapidly from

person to person until whole areas were affected. The name

tarantella, in use at the present time, applies both to a dance

still in vogue in Southern Italy and also to musical pieces

resembling in their stimulating measures those that were

necessary to rouse to activity the sufferer from tarantism in

the middle ages. In recent times the term tarantula has been

applied indiscriminately to many different kinds of large spiders

in no way related to Lycosa tarantula; and to at least one

Arachnid belonging to a distinct order. In most parts of

America, for example, where English is spoken, species of

Aviculariidae, or “Bird-eating” spiders of various genera, are

invariably called tarantulas. These spiders are very much

larger and more venomous than the largest of the Lycosidae,

and in the Southern states of North America the species of

wasps that destroy them have been called tarantula hawks.

In Queensland one of the largest local spiders, known as

Holconia immanis, a member of the family Clubionidae, bears

the name tarantula; and in Egypt it was a common practice

of the British soldiers to put together scorpions and tarantulas,

the latter in this instance being specimens of the large and

formidable desert-haunting Arachnid, Galeodes lucasii, a member

of the order Solifugae. Similarly in South Africa species of

the genus Solpuga, another member of the Solifugae, were employed

for the same purpose under the name tarantula. Finally

the name Tarantula, in a scientific and systematic sense, was

first given by Fabricius to a Ceylonese species of amblypygous

Pedipalpi, still sometimes quoted as Phrynus lunatus. (R. I. P.)

TARAPACÁ, a northern province of Chile, bounded N. by Tacna, E. by Bolivia, S. by Antofagasta, and W. by the Pacific. Area 18,131 sq. m. Pop. (1895) 89,751; (1902, estimated) 101,105. It is part of the rainless desert region of the Pacific coast of South America, and is absolutely without water except at the base of the Andes where streams flow down into the sands and are lost. In some of these places there is vegetation and water enough to support small settlements. The wealth of Tarapacá is in its immense deposits of nitrate of soda (found on the Pampa de Tamarugal, a broad desert plateau between the coast range and the Andes, which has an elevation of about 3000 ft.). The mining and preparation of nitrate of soda for export maintain a large population and engage an immense amount of capital. Silver is mined in the vicinity of Iquique, the capital. The ports of the province are Pisagua, Iquique and Patillos, from which “nitrate railways” run inland to the deposits. Tarapacá was ceded to Chile by Peru after the war of 1879–1883, and was organized as a province in 1884. TARARE, a town of east-central France, in the department of Rhone, on the Turdine, 28 m. W.N.W. of Lyons by rail. Pop. (1906) 11,643. It is the centre of a region engaged in the production of muslins, tar let ans, embroidery and silk-plush, and in printing, bleaching and other subsidiary processes. Till 1756, when the manufacture of muslins was introduced from Switzerland, the town lay unknown among the Beaujolais mountains. The manufacture of Swiss cotton yarns and crochet embroideries was introduced at the end of the 18th century; at the beginning of the 19th figured stuffs, open-works and zephyrs were first produced. The manufacture of silk-plush for hats and machine-made velvets was set up towards the end of the 19th century. A busy trade is carried on in corn, cattle, linen, hemp, thread and leather. TARASCON, a town of south-eastern France, in the department of Bouches-du-Rhone, 62 m. N.W. of Marseilles by rail. Pop. (1906) town, 5447; commune, 8972. Tarascon is situated on the left bank of the Rhone opposite Beaucaire, with which it is connected by a railway bridge and a suspension bridge. The church of St Martha, built in 1187–97 on the ruins of a Roman temple and rebuilt in 1379–1449, has a Gothic spire, and many interesting pictures in the interior. Of the original building there remain a porch, and a side portal flanked by marble columns with capitals like those of St Trophimus at Arles. The former leads to the crypt, where are the tombs of St Martha (1658), Jean de Gossa, governor of Provence under King René, and Louis II., king of Provence. The castle, picturesquely situated on a rock, was begun by Count Louis II. in the 14th century and finished by King René in the 15th, It contains a turret stair and a chapel entrance, which are charming examples of 15th-centuryy architecture, and fine wooden ceilings. The building is now used as a prison. The hôtel-de-ville dates from the 17th century. The civil court of the arrondissement of Arles is situated at Tarascon, which also possesses a commercial court, and fine cavalry barracks. The so-called Arles sausages are made here, and there is trade in fruit and early vegetables. In Tartarin de Tarascon, Alphonse Daudet has satirized the provincial life of Tarascon. Its uneventfulness