CHAP. II.

On the Magnetick Coition, and first on the

Attraction of Amber, or more truly, on the

Attaching of Bodies to Amber.

The page and line references given in these notes are in all cases first to the Latin edition of 1600, and secondly to the English edition of 1900.

108 ^ Page 47, line 15. Page 47, line 18. Græci vocant ἠλεκτρον, quia ad se paleas trahit. In this discussion of the names given to amber, Gilbert apparently conceives ἠλεκτρον to be derived from the verb ἑλκεῖν; which is manifestly a doubtful etymology. There has been much discussion amongst philologists as to the derivation of ἠλέκτρον or ἤλεκτρον, and its possible connection with the word ἠλέκτωρ. This discussion has been somewhat obscured by the circumstance that the Greek authors unquestionably used ἤλεκτρον (and the Latins their word electrum) in two different significations, some of them using these words to mean amber, others to mean a shining metal, apparently of having qualities between those of gold and silver, and probably some sort of alloy. Schweigger, Ueber das Elektron der Alten (Greifswald, 1848), has argued that this metal was indeed no other than platinum: but his argument partakes too much of special pleading. Those who desire to follow the question of the derivation of ἤλεκτρον may consult the following authorities: J. M. Gessner, De Electro Veterum (Commentt. Soc. Reg. Scientt. Goetting., vol. iii., p. 67, 1753); Delaunay, Mineralogie der Alten, Part II., p. 125; Buttmann, Mythologus (Appendix I., Ueber das Elektron), Vol. II., p. 355, in which he adopts Gilbert's derivation from ἕλκειν; Beckmann, Ursprung und Bedeutung des Bernsteinnamens Elektron (Braunsberg, 1859); Th. Henri Martin, Du Succin, de ses noms divers et de ses variétés suivant les anciens (Mémoires de l'Académie des Inscriptions et Belles-lettres, Tome VI., 1re série, 1re partie, 1860); Martinus Scheins, De Electro Veterum Metallico (Inaugural dissertation, Berlin, 1871); F. A. Paley, Gold Worship in relation to Sun Worship (Contemporary Review, August, 1884). See also Curtius, Grundzüge der griechischen Etymologie, pp. 656-659. The net result of the disputations of scholars appears to be that ἠλέκτωρ (he who shines) is a masculine form to which there corresponds the neuter form ἤλεκτρον (that which shines). Stephanus admits the accentuation used by Gilbert, ἠλέκτρον, to be justified from the Timæus of Plato; see <a href="#Nt148">Note</a> to p. 61.

109 ^ Page 47, line 16. Page 47, line 19. ἅρπαξ dicitur, & χρυσοφόρον.—With respect to the other names given to amber, M. Th. Henri Martin has written (see previous note) so admirable an account of them that it is impossible to better it. It is therefore given here entire, as follows:

- "Le succin a reçu chez les anciens des noms très-divers. Sans parler du nom de λυγκούριον, lyncurium, qui peut-être ne lui appartient pas, comme nous le montrerons plus loin, il s'est nommé chez les Grecs le plus souvent ἤλεκτρον au neutre,1 mais aussi ἤλεκτρος au masculin2 et même au féminin,3 χρυσήλεκτρος,4 χρυσόφορος5 et peut-être, comme nous l'avons vu, χαλκολίθανον; plus tard σούχιον6 ou σουχίνος7, et ἠλεκτριανὸς λίθος;8 plus tard encore βερενίκη, βερονίκη ou βερνίκη;9 il s'est nommé ἅρπαξ chez les Grecs établis en Syrie;10 chez les Latins succinum, electrum, et deux variétés, chryselectrum et sualiternicum ou subalternicum;11 chez les Germains, Gless;12 chez les Scythes, sacrium;13 chez les Egyptiens, sacal;14 chez les Arabes, karabé15 ou kahraba;16 en persan, káruba.17 Ce mot, qui appartient bien à la langue persane, y signifie attirant la paille, et par conséquent exprime l'attraction électrique, de même que le mot ἅρπαξ des Grecs de Syrie. En outre, le nom de haur roumi (peuplier romain) était donné par les Arabes, non-seulement à l'arbre dont ils croyaient que le succin était la gomme, mais au succin lui-même. Haur roumi, transformé en aurum par les traducteurs latins des auteurs arabes, et consondu mal à propos avec ambar ou ambrum, nom arabe latinisé de l'ambre gris, a produit le nom moderne d'ambre, nom commun à l'ambre jaune ou succin, qui est une résine fossile, et à l'ambre gris, concrétion odorante qui se forme dans les intestines des cachalots. On ne peut dire avec certitude si le nom de basse grécité βερνίκη est la source ou le dérivé de Bern, radical du nom allemand du succin (Bernstein). Quoi qu'il en soit, le mot βερνίκη a produit vernix, nom d'une gomme dans la basse latinité, d'où nous avons fait vernis.18"

- 1 Voyez Hérodote, III., 115; Platon, Timée, p. 80 c; Aristote, Météor., IV., 10; Théophraste, Hist. des plantes, IX., 18 (19), § 2; Des pierres, § 28 et 29; Diodore de Sic., V., 23; Strabon, IV., 6, no 2, p. 202 (Casaubon); Dioscoride, Mat. méd., I., 110; Plutarque, Questions de table, II., 7, § 1; Questions platoniques, VII., 1 et 7; Lucien, Du succin et des cygnes; le même, De Pastrologie, § 19; S. Clément, Strom. II., p. 370 (Paris, 1641, in-fol.); Alexandre d'Aphr., Quest. phys. et mor., II., 23; Olympiodore, Météor., I., 8, fol. 16, t. I., p. 197 (Ideler) et l'abréviateur d'Etienne de Byzance au mot Ηλεκτρίδες.

- 2 Voyez Sophocle, Antigone, v. 1038, et dans Eustathe, sur l'Iliade, II., 865; Elien, Nat. des animaux, IV. 46; Quintus de Smyrne, V., 623; Eustathe, sur la Périégèse de Denys, p. 142 (Bernhardy), et sur l'Odyssée, IV., 73; et Suidas au mot ὑάλη.

- 3 Voyez Alexandre, Problèmes, sect. 1, proœm., p. 4 (Ideler); Eustathe, sur l'Odyssée, IV., 73, et Tzetzès, Chiliade VI., 650.

- 4 Voyez Psellus, Des pierres, p. 36 (Bernard et Maussac).

- 5 Voyez Dioscoride, Mat. méd., I., 110.

- 6 Voyez S. Clément, Strom., II., p. 370 (Paris, 1641, in-fol.). Il paraît distinguer l'un de l'autre τὸ σούχιον et τὸ ἤλεκτρον, probablement parce qu'il attribue à tort au métal ἤλεκτρον la propriété attractive du succin.

- 7 Voyez le faux Zoroastre, dans les Géoponiques, XV., 1, § 29.

- 8 Voyez le faux Zoroastre, au même endroit.

- 9 Voyez Eustathe, sur l'Odyssée, IV., 73; Tzetzès, Chil. VI., 650; Nicolas Myrepse, Antidotes, ch. 327, et l'Etymol. Gud. au mot ἤλεκτρον. Comparez Saumaise, Exert. plin., p. 778.

- 10 Voyez Pline, XXXVII., 2, s. 11, no 37.

- 11 Voyez Pline, XXXVII., 2, s. 11-13, et Tacite, Germanie, ch. 45. La forme sualiternicum, dans Pline (s. 11, no 33), est donnée par le manuscrit de Bamberg et par M. Sillig (t. V., p. 390), au lieu de la forme subalternicum des éditions antérieures.

- 12 Voyez Tacite et Pline, ll. cc.

- 13 Voyez Pline, XXXVII., 2, s. 11, no 40, Comp. J. Grimm, Gesch. der deutsch. Sprache, Kap. x., p. 233 (Leipzig, 1848, in-8).

- 14 Pline, l. c.

- 15 Voyez Saumaise, De homon. hyles iatricæ, c. 101, p. 162 (1689, in-fol.).

- 16 Voyez Sprengel, sur Dioscoride, t. II., pp. 390-391.

- 17 Voyez M. de Sacy, cité par Buttmann, Mythologus, t. II., pp. 362-363.

- 18 Voyez Saumaise, Ex. plin., p. 778. Il n'est pas probable que le mot βερνίκη ou βερενίκη nom du succin dans la grécité du moyen âge, soit lié étymologiquement avec le nom propre βερενίκη, qui vient de l'adjectif macédonien βερένικος pour φερένικος.

110 ^ Page 47, line 17. Page 47, line 20. Mauri vero Carabem appellant, quià solebant in sacrificijs, & deorum cultu ipsum libare. Carab enim significat offerre Arabicè; ita Carabe, res oblata; aut rapiens paleas, vt Scaliger ex Abohali citat, ex linguâ Arabicâ, vel Persicâ.—The printed text, line 18, has "Non rapiens paleas," but in all copies of the folio of 1600, the "Non" has been altered in ink into "aut," possibly by Gilbert's own hand. Nevertheless the editions of 1628 and 1633 both read "Non." There appears to be no doubt that the origin of the word Carabe, or Karabe, as assigned by Scaliger, is substantially correct. As shown in the preceding note, Martin adopted this view. If any doubt should remain it will be removed by the following notes which are due to Mr. A. Houtum Schindler (member of the Institution of Electrical Engineers), of Terahan.

Reference is made to the magnetic and electric properties of stones in three early Persian lapidaries. There are three stones only mentioned, amber, loadstone, and garnet. The electric property of the diamond is not mentioned. The following extracts are from the Tansûk nâmah, by Nasîr ed dîn Tûsi, A.D. 1260. The two other treatises give the first extracts in the same words.

"Kâhrubâ, also Kahrabâ [Amber],

"Is yellow and transparent, and has its name from the property, which it possesses, of attracting small, dry pieces of straw or grass, after it has been rubbed with cloth and become warm. [Note. In Persian, Kâh = straw; rubâ = the robber, hence Kâhrubâ = the straw-robber.] Some consider it a mineral, and say that it is found in the Mediterranean and Caspian seas, floating on the surface, but this is not correct. The truth is that Kâhrubâ is the gum of a tree, called jôz i rûmî [i.e., roman nut; walnut?], and that most of it is brought from Rûm [here the Eastern Rome] and from the confines of Sclavonia and Russia. On account of its bright colour and transparency it is made into beads, rings, belt-buckles, &c. ... &c.

"The properties of attraction and repulsion are possessed by other substances than loadstone, for instance, by amber and bîjâdah,1 which attract straws, feathers, etc., and of many other bodies, it can be said that they possess the power of attraction. There is also a stone which attracts gold; it has a pure yellow colour. There is also a stone which attracts silver from distances of three or two yards. There are also the stone which attracts tin, very hard, and smelling like asafœtida, the stone attracting hair, the stone attracting meat, etc., but, latterly, no one has seen these stones: no proof, however, that they do not exist."

Avicenna (Ibn Sinâ) gives the following under the heading of Karabe (see Canona Medicinæ, Giunta edition, Venet., 1608, lib. ii., cap. 371, p. 336):

"Karabe quid est? Gumma sicut sandaraca, tendens ad citrinitatem, & albedinem, & peruietatem, & quandoque declinat ad rubedinem, quæ attrahit paleas, & [fracturas] plantarum ad se, & propter hoc nominatur Karabe, scilicet rapiens paleas, persicè.... Karabe confert tremori cordis, quum bibitur ex eo medietas aurei cum aqua frigida, & prohibet sputum sanguinis valde.... Retinet vomitum, & prohibet materias malas a stomacho, & cum mastiche confortat stomachum.... Retinet fluxum sanguinis ex matrice, & ano, & fluxum ventris, & confert tenasmoni."

Scaliger in De Subtilitate, Exercitatio ciii., § 12, the passage referred to by Gilbert says: "Succinum apud Arabas uocatur, Carabe: quod princeps Aboali, rapiens paleas, interpretatur" (p. 163 bis, editio Lutetiæ, 1557).

- 1 Bîjâdah is classified by Muhammad B. Mansûr (A.D. 1470) and by Ibn al Mubârak (A.D. 1520) under "stones resembling ruby"; the Tansûk nâmah describes it in a separate chapter. From the description it can be identified with the almandine garnet, and the method of cutting this stone en cabochon, with hollow back in order to display its colour better is specially mentioned. The Tansûk nâmah only incidentally refers to the electric property of the bîjâdah in the chapter on loadstone, but the other two treatises specially refer to it in their description of the stone. The one has: "Bîjâdah if rubbed until warm, attracts straws and other light bodies just as amber does"; the other: "Bîjâdah, if rubbed on the hair of the head, or on the beard, attracts straws." Surûri, the lexicographer, who compiled a dictionary in 1599, considers the bîjâdah "a red ruby which possesses the property of attraction." Other dictionaries do not mention the attractive property, but some authors confound the stone with amber, calling it Kâbrubâ, the straw-robber. The bîjâdah is not rubellite (red tourmaline) for it is described in the lapidaries as common, whereas rubellite (from Ceylon) has always been rare, and was unknown in Persia in the thirteenth century.

111 ^ Page 47, line 21. Page 47, line 25. Succinum seu succum.—Dioscorides regarded amber as the inspissated juice of the poplar tree. From the Frankfurt edition of 1543 (De Medicinali materia, etc.) edited by Ruellius, we have, liber i., p. 53:

Populus. Cap. XCIII.

"... Lachrymam populorum commemorant quæ in Padum amnem defluat, durari, ac coire in succinum, quod electrum vocant, alii chrysophorum. id attritu jucundum odorem spirat, et aurum colore imitatur. tritum potumque stomachi ventrisque fluxiones sistit."

To this Ruellius adds the commentary:

"Succinum seu succina gutta à succo dicta, Græcis ἤλεκτρομ [sic], esse lachryma populi albæ, vel etiam nigræ quibusdam videtur, ab ejusdem arboris resina. Dioscoridi et Galeno dicta differens et πτερυγοφόρος, id est paleas trahens, quoque vocatur, quantum ei quoque Galenus tribuit li. 37, ca. 9. Succinum scribit à quibusdam pinei generis arboribus, ut gummi à cerasis excidere autumno, et largum mitti ex Germania septentrionali, et insulis maris Germanici. quod hodie nobis est compertissimum: ad hæc liquata igni valentiore, quia à frigido intensiore concrevit. pineam aperte olet, calidum primo gradu, siccum secundo, stomachum roborat, vomitum, nauseam arcet. cordis palpitationi prodest. pravorem humorum generationem prohibet.

"Germani weiss und gelbaugstein et brenstein.

"Galli ambra vocant: vulgo in corollis precariis frequens."

In the scholia of Johann Lonicer in his edition of Dioscorides, we find, lib. i., cap. xcviii., De nigra Populo:

"ἄιγειρος, populus nigra ... idem electrum vel succinum αἱγείρου lachrymam esse adseverat [Paulus], cui præter vires quæ ab Dioscoride recensentur, tribuit etiam vim sistendi sanguinis, si tusum in potu sumatur. Avicennæ Charabe, ut colligitur ex Joanne Jacobo Manlio, est electrum hoc Dioscoridis, attestatur Brunfelsius. Lucianus planè nullum electrum apud Eridanum seu Padum inveniri tradit, quandoquidem ne populus quidem illa ab nautis ei demonstrari potuerit. Plinius rusticas transpadanas ex electro monilia gestare adfirmat, quum à Venetis primum agnoscere didicissent adversus nimirum vitia gutturis et tonsillarum. Num sit purgamentum maris, vel lachryma populi, vel pinus, vel ex radiis occidentis solis nascatur, vel ex montibus Sudinorum profluat, incertum etiam Erasmus Stella relinquit. Sudinas tamen Borussiorum opes esse constat."

Matthiolus (in P. A. Mattioli ... Opera quæ extant omnia, hoc est Commentarii in vi libros P. Dioscoridis de materia medica, Frankfurt, 1596, p. 133) comments on the suggestion of Galen that amber came from the Populus alba, and also comments on the Arabic, Greek, and Latin names of amber.

The poplar-myth is commemorated by Addison (in Italy) in the lines:

- No interwoven reeds a garland made,

- To hide his brows within the vulgar shade;

- But poplar wreathes around his temples spread,

- And tears of amber trickled down his head.

Amber is, however, assuredly not derived from any poplar tree: it comes from a species of pine long ago extinct, called by Göppert the pinites succinifer.

Gilbert does not go into the medicinal uses, real or fancied, that have been ascribed to amber in almost as great variety as to loadstone. Pliny mentions some of these in his Natural Historie (English version of 1601, p. 609):

"He [Callistratus] saith of this yellow Amber, that if it be worne about the necke in a collar, it cureth feavers, and healeth the diseases of the mouth, throat, and jawes: reduced into pouder and tempered with honey and oile of roses, it is soveraigne for the infirmities of the eares. Stamped together with the best Atticke honey, it maketh a singular eyesalve for to help a dim sight: pulverized, and the pouder thereof taken simply alone, or else drunke in water with Masticke, is soveraigne for the maladies of the stomacke."

Nicolaus Myrepsus (Recipe 951, op. citat.) gives a prescription for dysentery and diabetes confiding chiefly of "Electri vel succi Nili (Nili succum appellant Arabes Karabem)."

112 ^ Page 47, line 22. Page 47, line 26. Sudauienses seu Sudini.—Cardan in De Rerum Varietate, lib. iii., cap. xv. (Editio Basil., 1556, p. 152), says of amber:

"Colligitur in quadam penè insula Sudinorum, qui nunc uocātur Brusci, in Prussia, nunc Borussia, juxta Veneticum sinum, & sunt orientaliores ostiis Vistulæ fluuii: ubi triginta pagi huic muneri destinati sunt," etc. He rejects the theory that it consists of hardened gum.

There exists an enormous literature concerning Amber and the Prussian amber industry. Amongst the earliest works (after Theophrastus and Pliny) are those of Aurifaber (Bericht über Agtstein oder Börnstein, Königsberg, 1551); Goebel (De Succino, Libri duo, authore Severino Gœbelio, Medico Doctore, Regiomont., 1558); and Wigand (Vera historia de Succino Borussico, Jena, 1590). Later on Hartmann, P. J. (Succini Prussici Physica et civilis Historia, Francofurti, 1677); and the splendid folio of Nathaniel Sendel (Historia Succinorum corpora aliena involventium, Lipsiæ, 1742), with its wealth of plates illustrating amber specimens, with the various included fossil fauna and flora. Georgius Agricola (De natura Fossilium, liber iv.), and Aldrovandi (Musæeum Metallicum, pp. 411-412) must also be mentioned. Bibliographies of the earlier literature are to be found in Hartmann (op. citat.), and in Daniel Gralath, Elektrische Bibliothek (Versuche und Abhandlungen der Naturforschenden Gesellschaft in Danzig, Zweiter Theil, pp. 537-539, Danzig and Leipzig, 1754). See also Karl Müllenhoff, Deutsche Altertumskunde, vol. i., Zweites Buch, pp. 211-224, Zinn und Bernsteinhandel (Berlin, 1870), and Humboldt's Cosmos (Bohn's edition, London, 1860, vol. ii., p. 493).

The ancient Greek myth according to which amber was the tears of the Heliades, shed on the banks of the river Eridanus over Phaethon, is not alluded to by Gilbert. It is narrated in well-known passages in Ovid and in Hyginus. Those interested in the modern handling of the myth should refer to Müllenhoff (op. citat., pp. 217-223, der Bernsteinmythus), or to that delightful work The Tears of the Heliades, by W. Arnold Buffum (London, 1896).

113 ^ Page 47, line 30. Page 47, line 36. quare & muscos ... in frustulis quibusdam comprehensos retinet.—The occurrence of flies in amber was well known to the ancients. Pliny thus speaks of it, book xxxvii., chap. iii. (p. 608 of P. Holland's translation of 1601):

"That it doth destill and drop at the first very clear and liquid, it is evident by this argument, for that a man may see diverse things within, to wit, Pismires, Gnats, and Lizards, which no doubt were entangled and stucke within it when it was greene and fresh, and so remain enclosed within as it waxed harder."

A locust embedded in amber is mentioned in the Musæum Septalianum of Terzagus (Dertonæ, 1664).

Martial's epigram (Epigrammata, liber vi., 15) is well known:

- Dum Phaethontea formica vagatur in umbra

- Implicuit tenuem succina gutta feram.

See also Hermann (Daniel), De rana et lacerta Succino Borussiaco insitis (Cracov., 1580; a later edition, Rigæ, 1600). The great work on inclusa in amber is, however, that of Nathaniel Sendel. See the previous note.

Sir Thomas Browne must not be forgotten in this connexion. The Pseudodoxia (p. 64 of the second edition, 1650) says:

"Lastly, we will not omit what Bellabonus upon his own experiment writ from Dantzich unto Mellichius, as he hath left recorded in his chapter De Succino, that the bodies of Flies, Pismires and the like, which are said oft times to be included in Amber, are not reall but representative, as he discovered in severall pieces broke for that purpose. If so, the two famous Epigrams hereof in Martiall are but poeticall, the Pismire of Brassavolus Imaginary, and Cardans Mousoleum for a flie, a meer phancy. But hereunto we know not how to assent, as having met with some whose reals made good their representments." See also Pope's Epistle to Dr. Arbuthnot, line 169.

114 ^ Page 47, line 34. Page 47, line 40. Commemorant antiqui quod succinum festucas et paleas attrahit.—Pliny (book xxxvii., chap. ii., p. 606 of the English edition of 1601) thus narrates the point:

"Hee [Niceas] writeth also, that in Aegypt it [amber] is engendered.... Semblably in Syria, the women (saith hee) make wherves of it for their spindles, where they use to call it Harpax, because it will catch up leaves, straws, and fringes hanging to cloaths."

p. 608. "To come to the properties that Amber hath, If it bee well rubbed and chaufed betweene the fingers, the potentiall facultie that lieth within, is set on work, and brought into actual operation, whereby you shall see it to drawe chaffe strawes, drie leaves, yea, and thin rinds of the Linden or Tillet tree, after the same sort as loadstone draweth yron."

115 ^ Page 47, line 36. Page 47, line 42. Quod etiam facit Gagates lapis.—The properties of Jet were well known to the mediæval writers. Julius Solinus writes in De Mirabilibus, chapter xxxiv., Of Britaine (English version of 1587 by A. Golding):

"Moreover to the intent to passe the large aboundance of sundry mettals (whereof Britaine hath many rich mynes on all sides), Here is store of the stone called Geate, and ye best kind of it. If ye demaund ye beautie of it, it is a black Jewell: if the qualitie, it is of no weight: if the nature, it burneth in water, and goeth out in Oyle; if the power, rubbe it till it be warme, and it holdeth such things as are laide to it; as Amber doth. The Realme is partlie inhabited of barbarous people, who even frõ theyr childhoode haue shapes of divers beastes cunninglye impressed and incorporate in theyr bodyes, so that beeing engraued as it were in theyr bowels, as the man groweth, so growe the marks painted vpon him...."

Pliny describes it as follows (p. 589, English edition of 1601):

"The Geat, which otherwise we call Gagates, carrieth the name of a toune and river both in Lycia, called Gages: it is said also, that the sea casteth it up at a full tide or high water into the Island Leucola, where it is gathered within the space of twelve stadia, and no where else: blacke it is, plaine and even, of a hollow substance in manner of the pumish stone, not much differing from the nature of wood; light, brittle, and if it bee rubbed or bruised, of a strong flavour." (Book xxxvi., chap. xviii.)

In the Commentary of Joannes Ruellius upon Dioscorides, Pedanii Dioscoridis Anazarbei de medicinali materia libri sex, Ioanne Ruellio Suessionensi interprete ... (Frankfurt, 1543, fol., liber quintus, cap. xcii.) is the following description:

"In Gagatarum lapidum genere, præferendus qui celeriter accenditur, et odorem bituminis reddit. niger est plerunque, et squalidus, crustosus, per quam levis. Vis ei molliendi, et discutiendi. deprehendit sonticum morbum suffitus, recreatque uuluæ strangulationes. fugat serpentes nidore. podagricis medicaminibus, et a copis additur. In Cilicia nasci solet, qua influens amnis in mare effunditur, proxime oppidum quod Plagiopolis dicitur. vocatur autem et locus et amnis Gagas, in cujus faucibus ii lapides inveniuntur.

"Gagates lapis colore atro, Germanis Schwartzer augstein, voce parum depravata, dicitur. odore dum uritur bituminis, siccat, glutinat, digerit admotus, in corollis precariis et salinis frequens."

And in the Scholia upon Dioscorides of Joannes Lonicer (Marpurgi, 1643, cap. xcvii., p. 80) is the following:

"De Gagate Lapide. Ab natali solo, urbe nimirum Gagae Lyciae nomen habet. Galenus se flumen isthuc et lapidem non invenisse, etiamsi naui parua totam Lyciam perlustravit: ait, se autem in caua Syria multos nigros lapides invenisse glebosos, qui igni impositi, exiguam flammam gignerent. Meminit hujus Nicander in Theriacis nempe suffitum hujus abigere venenata."

There is also a good account of Gagates (and of Succinum) by Langius, Epistola LXXV., p. 454, of the work Epistolarum medicinalium volumen tripartitum (Francofurti, 1589).

116 ^ Page 47, line 39. Page 47, line 45. Multi sunt authores moderni.—The modern authors who raised Gilbert's wrath by ignorantly copying out all the old tales about amber, jet, and loadstone, instead of investigating the facts, were, as he says at the beginning of the chapter, some theologians, and some physicians. He seems to have taken a special dislike to Albertus Magnus, to Puteanus (Du Puys), and to Levinus Lemnius.

117 ^ Page 47, line 39. Page 47, line 46. & gagate.—The editions of 1628 and 1633 both read ex gagate.

118 ^ Page 48, line 14. Page 48, line 16. Nam non solum succinum, & gagates (vt illi putant) allectant corpuscula.—The list of bodies known to become electrical by friction was not quite so restricted as would appear from this passage. Five, if not six, other minerals had been named in addition to amber and jet.

(1.) Lyncurium. This stone, about which there has been more obscurity and confusion than about any other gem, is supposed by some writers to be the tourmaline, by others a jacinth, and by others a belemnite. The ancients supposed it to be produced from the urine of the lynx. The following is the account of Theophrastus, Theophrastus's History of Stones. With an English Version ..., by "Sir" John Hill, London, 1774, p. 123, ch. xlix.-l. "There is some Workmanship required to bring the Emerald to its Lustre, for originally it is not so bright. It is, however, excellent in its Virtues, as is also the Lapis Lyncurius, which is likewise used for engraving Seals on, and is of a very solid Texture, as Stones are; it has also an attractive Power, like that of Amber, and is said to attract not only Straws and small pieces of Sticks, but even Copper and Iron, if they are beaten to thin pieces. This Diocles affirms. The Lapis Lyncurius is pellucid, and of a fire Colour." See also W. Watson in Philos. Trans., 1759, L. i., p. 394, Observations concerning the Lyncurium of the ancients.

- (2.) Ruby.

(3.) Garnet. The authority for both these is Pliny, Nat. Hist., book xxxvii., chap. vii. (p. 617 of English edition of 1601).

"Over and besides, I find other sorts of Rubies different from those above-named;... which being chaufed in the Sun, or otherwise set in a heat by rubbing with the fingers, will draw unto them chaffe, strawes, shreads, and leaves of paper. The common Grenat also of Carchedon or Carthage, is said to doe as much, although it be inferiour in price to the former."

(4.) Jasper. Affaytatus is the authority, in Fortunii Affaitati Physici atque Theologi ... Physicæ & Astronomicæ cōsiderationes (Venet., 1549), where, on p. 20, he speaks of the magnet turning to the pole, likening it to the turning of a "palea ab Ambro vel Iaspide et hujuscemodi lapillis lucidis."

(5.) Lychnis. Pliny and St. Isidore speak of a certain stone lychnis, of a scarlet or flame colour, which, when warmed by the sun or between the fingers, attracts straws or leaves of papyrus. Pliny puts this stone amongst carbuncles, but it is much more probably rubellite, that is to say, red tourmaline.

(6.) Diamond. In spite of the confusion already noted, à propos of adamas (Note to p. 47), between loadstone and diamond, there seems to be one distinct record of an attractive effect having been observed with a rubbed diamond. This was recorded by Fracastorio, De sympathia et antipathia rerum (Giunta edition, Venice, MDLXXIIII, chap. v., p. 60 verso), "cujus rei & illud esse signum potest, cum confricata quædã vt Succinum, & Adamas fortius furculos trahunt." And (on p. 62 recto); "nam si per similitudine (vt supra diximus) fit hæc attractio, cur magnes non potius magnetem trahit, q' ferrum, & ferrum non potius ad ferrum movetur, quàm ad magnetem? quæ nam affinitas est pilorum, & furculorum cum Electro, & Adamante? præsertim q' si cum Electro affines sunt, quomodo & cum Adamante affinitatem habebunt, qui dissimilis Electro est?" An incontestable case of the observation of the electrification of the diamond occurs in Gartias ab Horto. The first edition of his Historia dei Semplici Aromati was publisht at Goa in India in 1563. In chapter xlviii. on the Diamond, occur these words (p. 200 of the Venetian edition of 1616): "Questo si bene ho sperimentato io più volte, che due Diamanti perfetti fregati insieme, si vniscono di modo insieme, che non di leggiero li potrai separare. Et ho parimente veduto il Diamante dopo di esser ben riscaldato, tirare à se le festuche, non men, che si faccia l'elettro." See also Aldrovandi, Musæum Metallicum (Bonon., 1648, p. 947).

Levinus Lemnius also mentions the Diamond along with amber. See his Occulta naturæ miracula (English edition, London, 1658, p. 199).

119 ^ Page 48, line 16. Page 48, line 18. Iris gemma.—The name iris was given, there can be little doubt, to clear six sided prisms of rock-crystal (quartz), which, when held in the sun's beams, cast a crude spectrum of the colours of the rainbow. The following is the account of it given in Pliny, book xxxvii., chap. vii. (p. 623 of the English version of 1601):

"... there is a stone in name called Iris: digged out of the ground it is in a certaine Island of the red sea, distant from the city Berenice three score miles. For the most part it resembleth Crystall: which is the reason that some hath tearmed it the root of Crystall. But the cause why they call it Iris, is, That if the beames of the Sunne strike upon it directly within house, it doth send from it against the walls that bee neare, the very resemblance both in forme and also in colour of a rainebow; and eftsoones it will chaunge the same in much varietie, to the great admiration of them that behold it. For certain it is knowne, that six angles it hath in manner of the Crystall: but they say that some of them have their sides rugged, and the same unequally angled: which if they be laid abroad against the Sunne in the open aire, do scatter the beames of the Sunne, which light upon them too and fro: also that others doe yeeld a brightnes from themselves, and thereby illuminat all that is about them. As for the diverse colours which they cast forth, it never happeneth but in a darke or shaddowie place: whereby a man may know, that the varietie of colours is not in the stone Iris, but commeth by the reverberation of the wals. But the best Iris is that which representeth the greatest circles upon the wall, and those which bee likest unto rainebowes indeed."

In the English translation of Solinus's De Mirabilibus (The excellent and pleasant worke of Julius Solinus containing the noble actions of humaine creatures, the secretes and providence of nature, the descriptions of countries ... tr. by A. Golding, gent., Lond., 1587), chapter xv. on Arabia has the following:

"Hee findeth likewise the Iris in the Red sea, sixe cornered as the Crystall: which beeing touched with the Sunnebeames, casteth out of him a bryght reflexion of the ayre like the Raynebowe."

Iris is also mentioned by Albertus Magnus (De mineralibus, Venet., 1542, p. 189), by Marbodeus Gallus (De lapidibus, Par. 1531, p. 78), who describes it as "crystallo simulem sexangulam," by Lomatius (Artes of curious Paintinge, Haydocke's translation, Lond., 1598, p. 157), who says, "... the Sunne, which casting his beames vpon the stone Iris, causeth the raine-bowe to appeare therein ...," and by "Sir" John Hill (A General Natural History, Lond., 1748, p. 179).

Figures of the Iris given by Aldrovandi in the Musæum Metallicum clearly depict crystals of quartz.

120 ^ Page 48, line 16. Page 48, line 18. Vincentina, & Bristolla (Anglica gemma siue fluor). This is doubtless the same substance as the Gemma Vincentij rupis mentioned on p. 54, line 16 (p. 54, line 18, of English Version), and is nothing else than the so-called "Bristol diamond," a variety of dark quartz crystallized in small brilliant crystals upon a basis of hæmatite. To the work by Dr. Thomas Venner (Lond., 1650), entitled Via Recta or the Bathes of Bathe, there is added an appendix, A Censure concerning the water of Saint Vincents Rocks neer Bristol (Urbs pulchra et Emporium celebre), in which, at p. 376, occurs this passage: "This Water of Saint Vincents Rock is of a very pure, cleare, crystalline substance, answering to those crystalline Diamonds and transparent stones that are plentifully found in those Clifts."

In the Fossils Arranged of "Sir" John Hill (Lond., 1771), p. 123, is the following entry: "Black crystal. Small very hard heavy glossy. Perfectly black, opake. Bristol (grottos, glass)" referring to its use.

The name Vincentina is not known as occurring in any mineralogical book. Prof. H. A. Miers, F.R.S., writes concerning the passage: "Anglica gemma sive fluor seems to be a synonym for Bristolla, or possibly for Vincentina et Bristolla. Both quartz and fluor are found at Clifton. In that case Vincentina and Bristolla refer to these two minerals, and if so one would expect Bristolla to be the Bristol Diamond, and Vincentina to be the comparatively rare Fluor spar from that locality."

At the end of the edition of 1653 of Sir Hugh Plat's Jewel House of Art and Nature, is appended A rare and excellent Discourse of Minerals, Stones, Gums, and Rosins; with the vertues and use thereof, By D. B. Gent. Here, p. 218, we read:

"We have in England a stone or mineral called a Bristol stone (because many are found thereabouts) which much resembles the Adamant or Diamond, which is brought out of Arabia and Cyprus; but as it is wanting of the same hardnesse, so falls it short of the like vertues."

121 ^ Page 48, line 18. Page 48, line 19. Crystallus.—Rock-crystal. Quartz. Pliny's account of it (Philemon Holland's version of 1601, p. 604) in book xxxvii., chap, ii., is:

"As touching Crystall, it proceedeth of a contrarie cause, namely of cold; for a liquor it is congealed by extreame frost in manner of yce; and for proofe hereof, you shall find crystall in no place els but where the winter snow is frozen hard: so as we may boldly say, it is verie yce and nothing else, whereupon the Greeks have give it the right name Crystallos, i. Yce.... Thus much I dare my selfe avouch, that crystall groweth within certaine rockes upon the Alps, and these so steepe and inaccessible, that for the most part they are constrained to hang by ropes that shall get it forth."

122 ^ Page 48, line 18. Page 48, line 20. Similes etiam attrahendi vires habere videntur vitrum ... sulphur, mastix, & cera dura sigillaris. If, as shown above, the electric powers of diamond and ruby had already been observed, yet Gilbert was the first beyond question to extend the list of electrics beyond the class of precious stones, and his discovery that glass, sulphur, and sealing-wax acted, when rubbed, like amber, was of capital importance. Though he did not pursue the discovery into mechanical contrivances, he left the means of that extension to his followers. To Otto von Guericke we owe the application of sulphur to make the first electrical machine out of a revolving globe; to Sir Isaac Newton the suggestion of glass as affording a more mechanical construction.

Electrical attraction by natural products other than amber after they have been rubbed must have been observed by the primitive races of mankind. Indeed Humboldt in his Cosmos (Lond., 1860, vol. i., p. 182) records a striking instance:

"I observed with astonishment, on the woody banks of the Orinoco, in the sports of the natives, that the excitement of electricity by friction was known to these savage races, who occupy the very lowest place in the scale of humanity. Children may be seen to rub the dry, flat and shining seeds or husks of a trailing plant (probably a Negretia) until they are able to attract threads of cotton and pieces of bamboo cane."

123 ^ Page 48, line 23. Page 48, line 25. arsenicum.—This is orpiment. See the Dictionary of metallick words at the end of Pettus's Fleta Minor.

124 ^ Page 48, line 23. Page 48, line 26. in convenienti cœlo sicco.—The observation that only in a dry climate do rock-salt, mica, and rock-alum act as electrics is also of capital importance. Compare page 56.

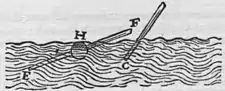

125 ^ Page 48, line 27. Page 48, line 31. Alliciunt hæc omnia non festucas modo & paleas.—Gilbert himself marks the importance of this discovery by the large asterisk in the margin. The logical consequence was his invention of the first electroscope, the versorium non magneticum, made of any metal, figured on p. 49.

126 ^ Page 48, line 34. Page 48, line 36. quod tantum siccas attrahat paleas, nec folia ocimi.—This silly tale that basil leaves were not attracted by amber arose in the Quæstiones Convivales of Plutarch. It is repeated by Marbodeus and was quoted by Levinus Lemnius as true. Gilbert denounced it as nonsense. Cardan (De Subtilitate, Norimb., 1550, p. 132) had already contradicted the fable. "Trahit enim," he says, "omnia levia, paleas, festucas, ramenta tenuia metallorum, & ocimi folia, perperam contradicente Theophrasto." Sir Thomas Browne specifically refuted it. "For if," he says, "the leaves thereof or dried stalks be stripped into small strawes, they arise unto Amber, Wax, and other Electricks, no otherwise then those of Wheat or Rye."

127 ^ Page 48, line 34. Page 48, line 38. Sed vt poteris manifestè experiri....

Gilbert's experimental discoveries in electricity may be summarized as follows:

- 1. The generalization of the class of Electrics.

- 2. The observation that damp weather hinders electrification.

- 3. The generalization that electrified bodies attract everything,

- including even metals, water, and oil.

- 4. The invention of the non-magnetic versorium or electroscope.

- 5. The observation that merely warming amber does not electrify it.

- 6. The recognition of a definite class of non-electrics.

- 7. The observation that certain electrics do not attract if roasted or

- burnt.

- 8. That certain electrics when softened by heat lose their power.

- 9. That the electric effluvia are stopped by the interposition of a sheet

- of paper or a piece of linen, or by moist air blown from the mouth.

- 10. That glowing bodies, such as a live coal, brought near excited amber

- discharge its power.

- 11. That the heat of the sun, even when concentrated by a burning mirror,

- confers no vigour on the amber, but dissipates the effluvia.

- 12. That sulphur and shell-lac when aflame are not electric.

- 13. That polish is not essential for an electric.

- 14. That the electric attracts bodies themselves, not the intervening air.

- 15. That flame is not attracted.

- 16. That flame destroys the electrical effluvia.

- 17. That during south winds and in damp weather, glass and crystal, which

- collect moisture on their surface, are electrically more interfered

- with than amber, jet and sulphur, which do not so easily take up

- moisture on their surfaces.

- 18. That pure oil does not hinder production of electrification or exercise

- of attraction.

- 19. That smoke is electrically attracted, unless too rare.

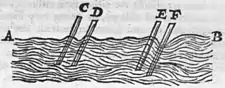

- 20. That the attraction by an electric is in a straight line toward it.

128 ^ Page 48, line 35. Page 48, line 39. quæ sunt illæ materiæ.—Gilbert's list of electrics should be compared with those given subsequently by Cabeus (1629), by Sir Thomas Browne (1646), and by Bacon. The last-named list occurs in his Physiological Remains, published posthumously in 1679; it contains nothing new. Sir Thomas Browne's list is given in the following passage, which is interesting as using for the first time in the English language the noun Electricities:

"Many stones also both precious and vulgar, although terse and smooth, have not this power attractive; as Emeralds, Pearle, Jaspis, Corneleans, Agathe, Heliotropes, Marble, Alablaster, Touchstone, Flint and Bezoar. Glasse attracts but weakely though cleere, some slick stones and thick glasses indifferently: Arsenic but weakely, so likewise glasse of Antimony, but Crocus Metallorum not at all. Saltes generally but weakely, as Sal Gemma, Alum, and also Talke, nor very discoverably by any frication: but if gently warmed at the fire, and wiped with a dry cloth, they will better discover their Electricities." (Pseudodoxia Epidemica, p. 79.)

In the Philosophical Transactions, vol. xx., p. 384, is A Catalogue of Electrical Bodies by the late Dr. Rob. Plot. It begins "Non solum succinum," and ends "alumen rupeum," being identical with Gilbert's list except that he calls "Vincentina & Bristolla" by the name "Pseudoadamas Bristoliensis."

129 ^ Page 49, line 25. Page 49, line 30. non dissimili modo.—The modus operandi of the electrical attractions was a subject of much discussion; see Cardan, op. citat.

130 ^ Page 51, line 2. Page 51, line 1. appellunt.—This appears to be a misprint for appelluntur.

131 ^ Page 51, line 22. Page 51, line 23. smyris.—Emery. This substance is mentioned on p. 22 as a magnetic body.

132 ^ Page 52, line 1. Page 51, line 46. gemmæ ... vt Crystallus, quæ ex limpidâ concreuit. See the <a href="#Nt121">note</a> to p. 48.

133 ^ Page 52, line 30. Page 52, line 32. ammoniacum.—Ammoniacum, or Gutta Ammoniaca, is described by Dioscorides as being the juice of a ferula grown in Africa, resembling galbanum, and used for incense.

"Ammoniack is a kind of Gum like Frankincense; it grows in Lybia, where Ammon's Temple was." Sir Hugh Plat's Jewel House of Art and Nature (Ed. 1653, p. 223).

134 ^ Page 52, line 38. Page 52, line 41. duæ propositæ sunt causæ ... materia & forma.—Gilbert had imbibed the schoolmen's ideas as to the relations of matter and form. He had discovered and noted that in the magnetic attractions there was always a verticity, and that in the electrical attractions the rubbed electrical body had no verticity. To account for these differences he drew the inference that since (as he had satisfied himself) the magnetic actions were due to form, that is to say to something immaterial—to an "imponderable" as in the subsequent age it was called—the electrical actions must necessarily be due to matter. He therefore put forward his idea that a substance to be an electric must necessarily consist of a concreted humour which is partially resolved into an effluvium by attrition. His discoveries that electric actions would not pass through flame, whilst magnetic actions would, and that electric actions could be screened off by interposing the thinnest layer of fabric such as sarcenet, whilst magnetic actions would penetrate thick slabs of every material except iron only, doubtless confirmed him in attributing the electric forces to the presence of these effluvia. See also p. 65. There arose a fashion, which lasted over a century, for ascribing to "humours," or "fluids," or "effluvia," physical effects which could not otherwise be accounted for. Boyle's tracts of the years 1673 and 1674 on "effluviums," their "determinate nature," their "strange subtilty," and their "great efficacy," are examples.

135 ^ Page 53, line 9. Page 53, line 11. Magnes vero....—This passage from line 9 to line 24 states very clearly the differences to be observed between the magnetical and the electrical attractions.

136 ^ Page 53, line 36. Page 53, line 41. succino calefacto.—Ed. 1633 reads succinum in error.

137 ^ Page 54, line 9. Page 54, line 11. Plutarchus ... in quæstionibus Platonicis.—The following Latin version of the paragraph in Quæstio sexta is taken from the bilingual edition publisht at Venice in 1552, p. 17 verso, liber vii., cap. 7 (or, Quæstio Septima in Ed. Didot, p. 1230).

"Electrum uero quæ apposita sunt, nequaquàm trahit, quem admodum nec lapis ille, qui sideritis nuncupatur, nec quicquā à seipso ad ea quæ in propinquo sunt, extrinsecus assilit. Verum lapis magnes effluxiones quasdam tum graves, tum etiam spiritales emittit, quibus aer continuatus & iunctus repellitur. Is deinceps alium sibi proximum impellit, qui in orbem circum actus, atque ad inanem locum rediens, ui ferrum fecum rapit & trahit. At Electrum uim quandam flammæ similem & spiritalem continet, quam quidem tritu summæ partis, quo aperiuntur meatus, foras eijcit. Nam leuissima corpuscula & aridissima quæ propè sunt, sua tenuitate atque imbecillitate ad seipsum ducit & rapit, cum non sit adeo ualens, nec tantum habeat ponderis & momenti ad expellendam aeris copiam, ut maiora corpora more Magnetis superare possit & uincere."

138 ^ Page 54, line 16. Page 54, line 18. Gemma Vincentij rupis.—See the <a href="#Nt120">note</a> to p. 48 supra, where the name Vincentina occurs.

139 ^ Page 54, line 30. Page 54, line 35. orobi.—The editions of 1628 and 1633 read oribi.

140 ^ Page 55, line 34. Page 55, line 42. in euacuati.—The editions of 1628 and 1633 read inevacuati.

141 ^ Page 58, line 21. Page 58, line 25. assurgentem vndam ... declinat ab F.—These words are wanting in the Stettin editions.

142 ^ Page 59, line 9. Page 59, line 9. fluore.—This word is conjectured to be a misprint for fluxu but it stands in all editions.

143 ^ Page 59, line 22. Page 59, line 25. Ruunt ad electria.—This appears to be a slip for electrica, which is the reading of the editions of 1628 and 1633.

144 ^ Page 60, line 7. Page 60, line 9. tanq materiales radij.—The suggestion here of material rays as the modus operandi of electric forces seems to foreshadow the notion of electric lines of force.

145 ^ Page 60, line 10. Page 60, line 12. Differentia inter magnetica & electrica.—Though Gilbert was the first systematically to explore the differences that exist between the magnetic attraction of iron and the electric attraction of all light substances, the point had not passed unheeded, for we find St. Augustine, in the De Civitate Dei, liber xxi., cap. 6, raising the question why the loadstone which attracts iron should refuse to move straws. The many analogies between electric and magnetic phenomena had led many experimenters to speculate on the possibility of some connexion between electricity and magnetism. See, for example, Tiberius Cavallo, A Treatise on Magnetism, London, 1787, p. 126. Also the three volumes of J. H. van Swinden, Receuil de Mémoires sur l'Analogie de Electricité et du Magnétisme, La Haye, 1784. Aepinus wrote a treatise on the subject, entitled De Similitudine vis electricæ et magneticæ (Petropolis, 1758). This was, of course, long prior to the discovery, by Oersted, in 1820, of the real connexion between magnetism and the electric current.