Quite obviously, the only way to read SSDs in the 14th century is to bring a computer. Or, actually, several computers. With great care, the computers will last for some twenty years, in which time one could hope, with an extraordinary amount of good luck, to push technological progress up to the 17th century -- you know, printing presses, telescopes, logarithms, basic algebra, some calculus, laws of motion, half-decent cannon, basic knowledge on the strength of materials. Use the time to transcribe the most important social and scientific principles of the modern world; then the computers will die, and everything in their memory will die with them.

Since questions like this appear from time to time, I thought it would be a good idea to set things straight. First of all, one cannot make an electronic computer in medieval Europe; what one can try is accelerate the technical and scientific progress to the point where making an electronic computer is possible: but, quite obviously, when reaching that point one will no longer be in medieval Europe. Technical and scientific progress cannot be decoupled from social evolution; a world which has the technology to build electronic computers is not a medieval world.

Why do I say that a world which has the technology to make electronic computers cannot possible resemble medieval Europe? For two obvious reasons: first, in a world with advanced technology there are lots and lots of literate people and lots and lots of books; and second, a world with advanced technology must by necessity be based on some sort of modern economy, either a Soviet-style planned economy, or a free market economy, but in any case nothing like the sluggish medieval economy. When a civilization reaches the point where the vast majority of people are literate and numerate and where most people work for a wage that civilization is way past feudalism.

When thinking of modern technology one must always keep in mind that it is but the top of vast mountain of work and knowledge; for the engineers who design and make, let's say, microprocessors rely on many other people to run the factories, and to make the wafers, and to design and make the photoengraving machines, and the measurement devices, and the artificial light sources, and the office buildings, and the vehicles, and the electric power grid, and the transportation networks and so on and so forth.

For a gentle introduction to the modern technological pyramid one is strongly urged to read Leonard Read's 1958 essay I, Pencil, in which the pencil, speaking in the first person, "details the complexity of its own creation, listing its components (cedar, lacquer, graphite, ferrule, factice, pumice, wax, glue) and the numerous people involved, down to the sweeper in the factory and the lighthouse keeper guiding the shipment into port" (Wikipedia). It's a short but definitely illuminating piece, and, moreover, it's available on line from multiple sources:

I, Pencil, simple though I appear to be, merit your wonder and awe, a claim I shall attempt to prove. In fact, if you can understand me—no, that's too much to ask of anyone—if you can become aware of the miraculousness which I symbolize, you can help save the freedom mankind is so unhappily losing. I have a profound lesson to teach. And I can teach this lesson better than can an automobile or an airplane or a mechanical dishwasher because—well, because I am seemingly so simple.

Simple? Yet, not a single person on the face of this earth knows how to make me. This sounds fantastic, doesn't it? Especially when it is realized that there are about one and one-half billion of my kind produced in the U. S. A. each year.

On to the practicalities.

The practicalities are of two kinds: practicalities related to the development of the story, and practicalities related to the verisimilitude of the world.

When developing the story it is very helpful to be aware of similar stories which have already been told. It is simply a good use of the author's time to read similar stories, so that they can benefit from the work of previous authors who worked in the field. The field in question is a subgenre of alternate history, characterized by describing the changes brought about by one or more modern people who find themselves in a pre-modern world.

It all begins with L. Sprague de Camp and his 1939 novel Lest Darkness Fall. American archaeologist Martin Padway is transported to Rome in the year 535 CE. One thing leads to another and he finds himself ruling Ostrogothic Italy. In a remarkable scene, the novel addresses the clash between modern economic expectation and the sad reality of the early Middle Ages. The hero coaxes an artisan to make a crude printing press and starts printing a newspaper; in the 6th century there was no paper in Europe, so the newspaper was naturally printed on vellum. The first issue goes out, but when the hero want to print a second issue his vellum suppliers inform him that he has used all the vellum available in central Italy, and he must wait at least half a year to get more from distant suppliers.

A necessary step are the entertaining (if maybe sexist, insensitive, and, possibly, quite badly written) adventures of Leo Frankowski's hero, Conrad Stargard, The Cross-Time Engineer (1986). A Polish engineer (from the People's Republic of Poland, no less!) is sent back in time to 13th century Poland, where he kick-starts an industrial revolution of sorts, becomes a powerful nobleman and generally messes up historical lines. The series is notable for the attempt to establish a plausible sequence of technological developments; the above-mentioned defects start to crowd out the good parts as the series progresses, so by Lord Conrad's Lady one is advised to skim and concentrate only on the technical aspects.

Eric Flint and many others put a lot, and I mean a lot, of effort into developing the Ring of Fire shared universe. A mid-size American town is transported from 1990s West Virginia to war-ravaged 1632 Thuringia. They immediately proceed to meddle in the Thirty Years' War, and to introduce great social and technological change. This shared universe is remarkable for the vast amount of research, with Eric Flint and his many many co-authors trying to make sure that each and every step in technological development was indeed possible, or at least not utterly impossible. One is well-advised to read the books and spend some time in the forum dedicated to the exploration of technologies.

Then there are many other more-or-less well-known works in this subgenre; I will only add S. M. Stirling's Nantucket series, beginning with Island on the Sea of Time (1998). Modern day Nantucket is transported in the 2nd millennium before the common era, and the inhabitants proceed to do their best to uplift the world around them, both socially and technologically. The plausibility of the developments is well-maintained, even if not raising to the high standards of 1632 and its sequels.

When plotting out the technological developments which go from the point of departure, be it the 2nd millennium BCE, or the 6th century CE, or the 14th century, or the 17th, up to something resembling the modern world, one must always remember that the modern world lives in the age of machines. To make the machines which make the stuff available in the modern world one first needs to make the machines which made the machines, and the machines which made the machines which made the machines, and so on up to many layers deep.

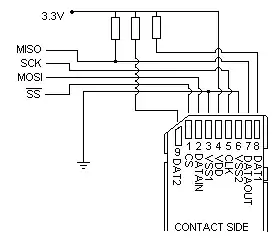

To concentrate on a specific example, let's consider the USB cable which connects the SSD device to the computer. The cable. Quoting from the standard describing USB cables and connectors (USB CabCon Workgroup, Universal Serial Bus 3.1 Legacy Connectors and Cable AssembliesCompliance Document, version 1.1, 2018):

Low Level Contact Resistance: 30 mΩ maximum initial for the Power (VBUS) and Ground (GND) contacts and 50 mΩ maximum initial for all other contacts when measured at 20 mV maximum open circuit at 100 mA.

Dielectric Withstanding Voltage: The dielectric must withstand 100 VAC (RMS) for one minute at sea level after the environmental stress defined in EIA 364-1000.01.

Cable Assembly Voltage Drop: At 900mA: 225mV max drop across power pair (VBUS and GND) from pin to pin (mated cable assembly).

Contact Capacitance: 2 pF maximum unmated, per contact. D+/D- contacts only.

Propagation Delay: 10ns maximum for a cable assembly attached with one or two Micro connectors and 26ns maximum for a cable assembly attached with no Micro connector. 200 ps rise time. D+/D-lines only.

Propagation Delay Intra-pair Skew: 100 ps Maximum. Test condition: 200 ps rise time. D+/D-lines only.

If you don't hit those specifications, the cable won't work. You must achieve the specs. There is no loophole.

Let's select the propagation delay. In order to make an USB cable one needs to be able to measure time with an accuracy of at least 10 ps. In 10 picoseconds light travels 3 mm, about one eighth of an inch. How does one approach the problem of designing and making a device which is able to measure the time in which light travels 3 millimeters? I have no idea; there are no more than two or maybe three people in a million who have a working acquaintance with designing and making such devices; and those rare people have no idea how make the wires, or the pins; or how to program the microcontrollers; etc.

How fast could technological development be pushed? That is to say, in real history the world took some seven hundred years to progress from the fourteenth century to the age of smartphones; how quickly can one imagine that this journey can be made? I'd say that with a lot of luck and dedication, and with quasi-divine guidance, it could be shortened to maybe three to four hundred years if all pitfalls are magically avoided. The reasoning is simple:

The last hundred years or so cannot be shortened; from the early twentieth century onwards technology progressed at breakneck pace, and there is no reasonable way to make it go faster. Remember that when the first people set foot on the Moon there were people alive, even in developed countries, which had been born before Edison invented his lightbulb. When Apple introduced the iPhone, there were people alive, even in developed countries, who had been born at a time when the shortest time to cross the Atlantic was measured in days.

The 19th century might be condensed in 75 years; to condense it further would stretch the societal evolution beyond breaking point. The 19th century began with Napoleon conquering Europe on horseback and ended with telegraph lines circling the globe; it began with the U.S.A. issuing letters of marque to privateers in their War of 1812 with the United Kingdom, and ended with global trade networks; it began with all European powers attempting to suppress the French Republic and ended well on the way towards universal suffrage in most civilized countries. That's some 175 years up to this point.

The 18th century might be condensed in 50 years, but not more. In real history, the 18th century saw tremendous advances in mathematics and in physics. Luminaries such as Leonhard Euler, Pierre-Simon Laplace, and the Bernouillis were pushing mathematics forward at the maximum speed human mind is capable of; going more than two times faster is inconceivable. That's 225 years up to this point.

The 17th century saw the transition from not having any physics to speak of to having decent physics. Maybe it could be condensed in 75 years, maybe not, but definitely not less. Remember that in real history the 17th century saw the discovery of calculus and the laws of motion, analytic geometry, and logarithms. The entire idea of a computable universe was born in the 17th century. That's 300 years already.

And then one must necessarily add some time to allow for developing the printing press, and introducing basic algebra, and printing enough books to lift people from the absolute darkness of the Middle Ages to the first lights of dawn...