Let us suppose that we have a normal human being without a tail. If we focus on the pelvic skeletal area, we can see the vestigial remnants of the tail which has devolved from our distant ancestors, in the form of the coccyx.

Now, the OP proposes that we add a substantial tail to this basic body plan, a tail that is as capable and useful to its owner as a kangaroo's is to its owner, capable of supporting the being's full weight and providing propulsion in both terrestrial and aquatic locomotion. The OP is correct in believing that adding such a tail would not be as simple as replacing the coccyx with the far more substantial appendage desired.

Why wouldn't we be able to just 'whack on' a big tail and call it a day? What would we have to do to make it work?

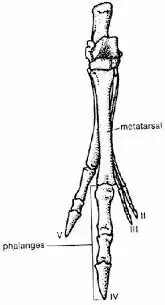

Consider the dimensions of this new tail. As any tail, it would consist of an extension of the vertebral column beyond the pelvis. In order to be able to support its owner's full weight and contribute to locomotion, it would have to have vertebrae that are robust enough to support the load, with muscle attachment processes big enough to anchor strong muscles. It would have to be at least as long as the leg plus the length of the foot - it would not support its owner's weight directly on its tip, but on at least twenty to forty centimeters of the end of the tail, almost like an extra foot, much as kangaroos use their tails.

With all this muscle and bone, we are looking at a substantial, massive appendage, with vertebrae roughly the same thickness as the lumbar vertebrae, surrounded by muscle that might make it as much as ten centimeters in diameter where it emerges from the pelvis. Unlike the picture of the artificial tail, it would emerge from the pelvis in line with the spine, not at right-angles to it.

This extra mass of muscle and bone would not come without consequences. The main consequence would be the alteration of the pelvic opening. Naively, this tail would 'bulk up' the coccyx on both sides, but this would result in it projecting into the pelvic girdle. For kangaroos, which give birth to offspring that weigh a few grams, this is not an issue, but for a human, which gives birth to offspring weighing five kilograms or more, with heads that have a diameter of ten centimeters, obstructing the pelvic opening could be fatal for both mother and child. This could be solved by moving the pelvic girdle ventrally so that its opening was unobstructed. This would result in the lower back appearing not almost flat from side to side as in modern humans, but with a rather more projecting bump on the lower back. At the very least, this would make lying supine more difficult, as the pelvis would tend to roll to one side or the other.

The next problem is that of locomotion. Unless the tail is even more bulky and muscular than I have described, it would not be used as a means of propulsion when walking or running. Fully tripodal locomotion involving the tail would be awkward enough that it is unlikely to evolve at this point. However, the presence of this weighty, bulky appendage would not be without its effects.

When walking and running, if the pelvic spine was vertical as it is in modern humans, a tail of this bulk would collide with the legs and the ground unless it was held up and to the rear. However, in that case, the weight of the tail behind its owner would shift the centre of mass backwards unless the torso was moved forward to compensate, resulting in a forward-leaning posture when walking or running. In fact, this would likely lead to the natural position of the legs being not directly in line with the torso, but being at a slight angle. This change would be reflected in the shape of the pelvis, with a slightly different shape to the pelvic bones to allow for the altered stance.

Having such a tail would mean that when stationary, the being could lean back on their tail, holding their torso fully erect in a tripodal stance, almost as if they were carrying a tall, narrow unipod seat around with them. As humans' upright stance likely evolved in order to see over tall grass in a plains environment, this tail would assist in such a posture, and allow a lookout to maintain a more comfortable stance while standing watch.

Given the strength of the tail, it would be capable of pushing its owner forward from a standing position, making the transition from standing to walking or running easier and more rapid, and would also allow a powerful braced two-footed kick as practised by modern kangaroos.

Given sufficient lateral musculature in the tail, it could contribute to aquatic locomotion to a small degree, given that in humans, the bulk of the power when swimming is provided by the upper body. This musculature would also enable the tail to be used as a weapon, to be swung about to bludgeon an enemy, as well as its use as a brace to strengthen a kick.

The tail is unlikely to be prehensile, given that African monkeys do not use their tails for grasping, while only South American monkeys use their tails in that fashion. Tailed Humans, probably being evolved from African monkeys and apes, would be unlikely to have prehensile tails due to that ancestry. However, the OP may be considering an alternative evolutionary path that allows for a prehensile, grasping tail.

Should this tail be prehensile, its strength would allow it to be used for crude grasping, and to help anchor an object being worked upon by the more dexterous hands.

The last significant difference in anatomy would be in the brain. In contrast to modern humans, these tailed humans would have a slightly different brain structure in order to provide the motor output from and sensory input to the tail. It wouldn't be a particularly major difference, but would likely be enough that an expert could tell the difference between a modern human and a tailed human from their gross brain anatomy, especially if the tail was prehensile.

The energy for this tail could easily be provided for by a modern human's digestive system, so there would be no need for any significant change in dentition, gastrointestinal or cardiopulmonary anatomy.

There would be other consequences to this change in anatomy, including likely alterations in the manner of copulation, preferred sleeping positions, furniture and transport design, and other sociological implications, but these go beyond the scope of the OP's question.