To give an example, how long would all humans have to leave the earth for a large part of the biodiversity and the original atmosphere to be restored, the oceans to recover, the fish population to increase, etc. Additional information: In my mind game, it is a controlled "leaving" of the earth, that is, dangerous industrial plants with chemicals or power plants would be shut down in a controlled manner.

3 Answers

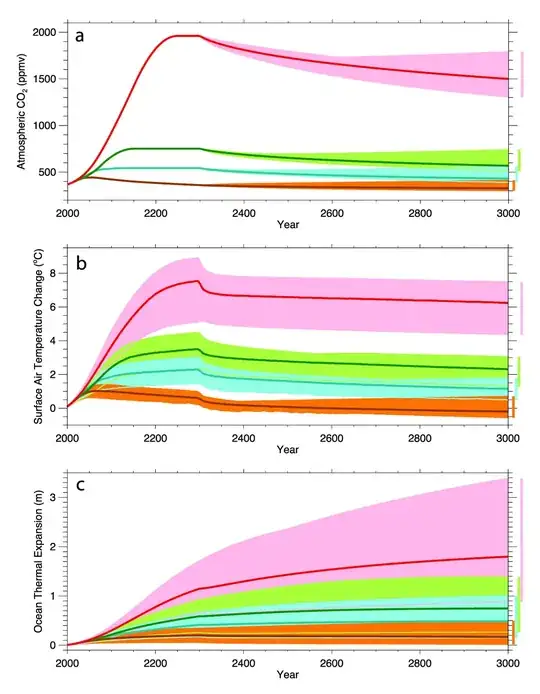

Carbon dioxide in the biosphere would normalize within roughly 400 years, but it would take thousands of years for the temperature to return to pre-industrial levels

If humans left the planet and stopped burning fossil fuels, making cement, and cutting down trees, the carbon cycle would result in a gradual reduction in atmospheric CO2.

From The Royal Society, citing Zickfield et al 2013:

If emissions of CO2 stopped altogether, it would take many thousands of years for atmospheric CO2 to return to “pre-industrial” levels due to its very slow transfer to the deep ocean and ultimate burial in ocean sediments. Surface temperatures would stay elevated for at least a thousand years, implying a long-term commitment to a warmer planet due to past and current emissions. Sea level would likely continue to rise for many centuries even after temperature stopped increasing.

The orange line across the bottom in the chart below shows what would happen in a scenario with aggressive emissions reductions, reaching zero within 50 years.

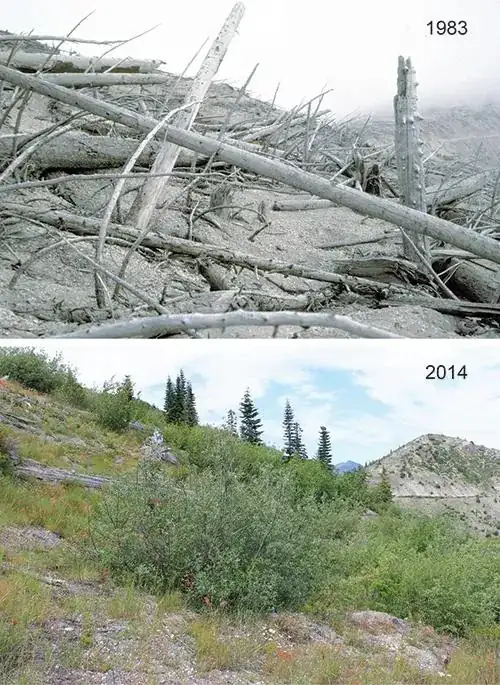

Individual ecosystems would take much less time to recover

Despite the millenia-long impacts of greenhouse gas emissions, ecosystems would recover much more quickly from the acute impacts of humanity. Consider Mt. St. Helens. The volcanic eruption of Mt. St. Helens in May 1980...

[...] initiated several catastrophic events over the next several minutes. The resulting colossal landslide smothered 60 square kilometers of river valley to a mean depth of 45 meters, obstructed tributaries to the North Fork Toutle River [...], and blocked the outlet of Spirit Lake at the foot of the volcano. An associated energy blast from the eruption unleashed a scorching cloud of rocky debris known as a pyroclastic density current [...] that swept over 600 square kilometers of rugged mountain terrain, removing, toppling, and singeing tracts of forest. Parts of that cloud also sped down the volcano’s snowclad east and west flanks, triggering meltwater flash floods that swept up sediment to become large, swift volcanic mudflows (lahars) that traveled many tens of kilometers downstream.

This obviously doesn't have anthropogenic causes, but it gave us the opportunity to study how quickly an ecosystem recovers after being completely destroyed:

After the eruption, ecologists quickly discovered that biological legacies (surviving plants and animals) from pre-eruption ecosystems persisted and were widely distributed; even some of the most heavily affected landscapes were not as sterile as initially assumed. The seasonal timing of the eruption and its time of day played important roles in determining which plants and animals lived or died; many organisms in subalpine lakes and on hillsides, protected beneath snow or ice, were spared the brunt of eruptive forces, for example, and nocturnal animals were in their dens. Those protections resulted in numerous patches of surviving organisms embedded within a vast expanse of disturbed land.

- 161

- 4

-

1If I get the chance I'll also add something about ocean acidification, as the oceans will probably be the slowest to recover. – LShaver Oct 29 '21 at 16:18

It won't. It will be something different. But, natural processes can take over in a short time. Look at what is happening in Chernobyl. Climate change can be quickly reversed with a super volcano eruption if there is no industrial pollution.

You might want to look at the Milankovitch cycles which indicate when we should be going into another ice age. https://climate.nasa.gov/news/2948/milankovitch-orbital-cycles-and-their-role-in-earths-climate/ It also may help to look at how animal husbandry has affected climate change (which started when we started farming). https://ehp.niehs.nih.gov/doi/10.1289/ehp.11034

Most of the petroleum and coal stores will never be restored. That carbon was trapped before some of the current fungi evolved to rot wood and plants. While we find oil in river deltas, that is much smaller amounts than what we have used.

You have to look not just at the dangerous chemicals, but also the nuclear waste. Some of that will take millions of years to decay to harmless. We would need to store that in a place where the decay doesn't harm the environment. That is currently not happening. (And we can argue if we even know how.)

- 5,653

- 1

- 7

- 18

-

One way it will never recover is extinction. Even if all humans vanished today, the Dodo bird is never coming back. – Ryan_L Oct 29 '21 at 16:23

-

2Saying millions of year to decay to harmless overstates the risk considerably. Most of the dangerous radiation from fission piles decays to low radiation risk in hundreds of years. e.g. Cs-137 as Sr-90 are the real long-term dangerous products, both have half-lives of about 30 years, decaying to almost nothing within 10 or at most 20 half-lives (depending on your risk-definition). Pu-239 is slower to decay (about 24K years), but radiation for such long-lived materials is such that they are not that dangerous to handle. Scary stuff, but not as scary as frequently characterized. – Gary Walker Oct 29 '21 at 17:54

-

1Nuclear waste has a negligible ecological impact compared to all the other human activities. Quantities are tiny compared to other wastes and toxic products, and they are concentrated in a small number of very small areas. – John Doty Oct 29 '21 at 19:21

For the greater part, very quickly indeed.

On the scale of several years to a few decades.

The longest to recover will be the air's chemical balance (CO2), and even that is still well within normal range, the Earth has had more (lots more) CO2 at times.

Also rather slow to recover fully is the chemical contamination of the oceans, especially floating plastic and microplastic. The is so much of it, and the breakdown process is so slow, that it will take decades to halve itself and a few millenia before all traces in open water is gone.

The true recovery of Old Forest regions will take several hundred years. Only a couple dozen years to be dense regions of lush trees, but the full richness of a forest ecosystem takes about 3 generations of the trees in it to settle down, and when your trees as 200-600-year life Oaks, you need to be patient.

But for the greater part?

Consider Chernobyl.

It's already been 35 years, and the worst nuclear catastrophe in history (by a couple magnitudes!) is still a radioactive wasteland that looks like this:

obviously That terrain is never going to recover, is it?

(Image from Palieski state radioecological reserve, 11 km from ground zero of Chernobyl. And downwind during the weeks following the fire.)

- 26,325

- 3

- 63

- 129

-

2I was considering citing the case of Chernobyl in my answer, but this meta-analysis indicates that there actually isn't enough research to say if the area has "recovered" or not. There's reason to believe that wildlife is simply moving to a place without people, then suffering shorter lifespans due to the radiation, resulting in a net loss of biodiversity when looking at the surrounding area. – LShaver Oct 29 '21 at 15:59

-

@LShaver that's a bit of true, and a truckload of cow manure. For example, the trees in that region are most particularly know for their habit of not migrating to better pastures, yet... there they are. Bigger, denser and (mostly) healthier than anywhere else. There have been significant damage and mutations and increased deathrate in the years immediately following the disaster. But right now, that zone of Earth is better off than almost anywhere else with compatible climate. It. Is. Recovering. And it doing so quickly. – PcMan Oct 29 '21 at 16:03

-

1My point is that wildlife is recovering from the humans that used to live there, now that they've left -- not the Chernobyl disaster (which is still killing wildlife). I suppose it's more nuance than anything. – LShaver Oct 29 '21 at 16:25

Rockets make lots of gases, atmosphere will be so much changed that most fauna and flora dissapear. Maybe some bacteries survive exodus.

– Kamitergh Oct 29 '21 at 09:46