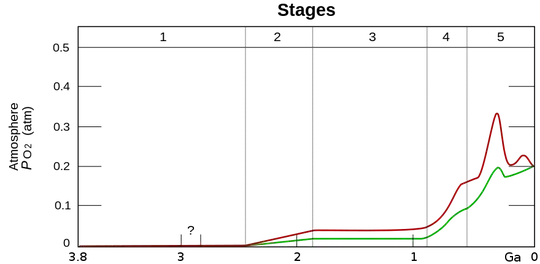

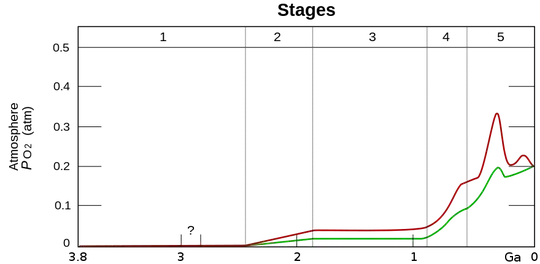

As far back as the oxygen content allows

The limit seems to be 500 Mya.

(Image source: geologic history of oxygen)

500 Mya, an event known as SPICE caused a dramatic shift in atmospheric O2. Oxygen content in the oceans dropped and content in the air rose, probably due to a mass die-off of plankton where other photosynthetic organisms stepped in to fill the niche, pulling CO2 from the atmosphere and pumping out O2. During this 4-8 million year period, atmospheric O2 rose to 10-28% oxygen by volume, compared to the present 21%, and compared to the levels at what is likely the highest-elevation settlement possible for high-altitude acclimatized humans, La Rinconada, Peru, at ~10% oxygen by volume. (At less than this, hypoxia and cognitive failure sets in.)

500 Mya was during the Cambrian explosion when most animal phyla emerged. So, no dinosaurs to contend with. Your traveler will eat, drink, and thrive on plants and pond scum for a year, with an occasional arthropod snack (all assuming no toxic qualities).

If the necessary proteins or amino acids aren't present in Cambrian-era life (if inedible or without nutrients), then the traveler could possibly train for and endure a year-long fast, staking out in a cave somewhere wondering to himself why he signed up for this bullsh--

(In reality, this likely wouldn't work. The human body does not store all the nutrients that it needs.)

Other eras of high-oxygen content:

There is evidence that oxygen content 1,400 Mya was sufficient enough for animal respiration, at ~4% present-day levels, though not necessarily large animal respiration (such as us humans). It should be noted that those levels were appropriate for the animals of the time.

The oxygen levels required for early animal respiration were lower than those needed to sustain large motile animals and were probably ≤1% PAL (present atmospheric levels)

So, unless your traveler is an immotile bacterium, this likely isn't relevant.

Despite its name, the Great Oxygenation Event saw oxygen levels at 0.001% of their present-day levels (while air density was less than half what it is today). What makes the event noteable is that quantities of oxygen produced as a photosynthetic by-product of cyanobacteria began to exceed the quantities of chemically reducing materials, and not any particular overabundance of oxygen.

Finding information about the evolution of atmospheric density is hard (this isn't my subject), but the general trend seems to be that Earth's early atmospheres were less massive than the present-day. At least half to nearly a quarter as massive. Less oxygen mass at less oxygen concentrations per volume means less habitability for larger animals.