The probability that any well-specified set of arbitrarily selected initial conditions is the steady state which would arise from those initial conditions is zero, and the probability that it would have arisen from any plausible previous set of initial conditions is also zero.

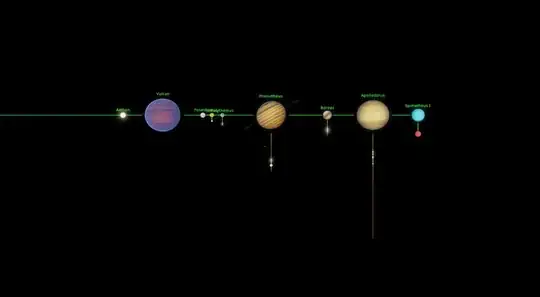

Here, there are some obvious problems. Just to start, Planet B is much too close to its star. .016AU is about 3 solar radii. There's no way a planet would have formed there, and even if we get a wizard to put a planet there with an huge tangent velocity so that it can keep from falling into the sun, it's not long for the world. Here's a photo of our star having a coronal mass ejection with your planet's relative position edited in that should illustrate that point.

However, the obvious problems are ultimately secondary. The real problem, both here and in your atmospheric composition questions, is that you've come to a false intuition about how long-lasting physical systems like atmospheres and planetary systems can be specified - that the lists of facts about real systems that you can find in reference books are lists of mostly unrelated facts that could each be otherwise than it is without changing all the others. This is not an unreasonable intuition, as it's true about many things in the world of regular experience, but it is false for atmospheres and planetary systems.

If we were to reduce your solar system to just A, G, and H - which look about right to me, we would be absolutely certain to be wrong. The reason is time.

For something to be a description of a star system or an atmosphere or a planet is for it to be a description of something very, very old, which is made out of things that are themselves very, very old, as a result of processes spanning billions of years. Like a crime scene tells a story of the past few hours, a solar system or an atmosphere tells a story of the past few billion years. If you want to make up a believable crime scene, you need to be able to explain it with a believable story of how human beings and an urban environment interacted over a few hours, which you can base on an intuitive simulation of the way humans interact with their environment based on long exposure to humans and human environments. The more you specify the crime scene, the better your simulation has to be for all the facts to line up for your story.

If you want to make up a believable solar system or atmosphere or planet or star, you need to be able to explain it with a believable story based on how matter interacted with gravity, chemistry, and nuclear chemistry over a few billion years. Most people are really bad at simulating that with their intuitions, unless you're a professional astrophysicist. If you just make up numbers for planetary orbits, masses, chemical compositions, temperatures, pressures, etc, the more you specify them, the more they're simply guaranteed to be wrong. The only ways out are to be vague, to do the simulation (or ask an expert to do the simulation for you), or to not care about being right in the first place.

Realistic sci-fi is written by combining options 1 and 2. Fantastical sci-fi is written by taking option 3.

There's nothing strictly wrong with being very specific and also being completely wrong, if you don't care about being right but you want characters who care about specifics. I personally find it grating in Star Trek, but I can't argue with the fact that it's worked out reasonably well for the franchise for 60 years.