No... except

First of all, your casual human might point to the leaf of a plant and say, "that's green." Your alien will likely say something along the lines of "Q'riik, naquooba ERK!" Now, we're tempted to assume that something in there, probably the "ERK!" part, means "green." Except when your human mumbles "that dumb alien is a greenhorn" at the same time the alien says, "knwumbbu choomahn D'nkrump" and where are we then?

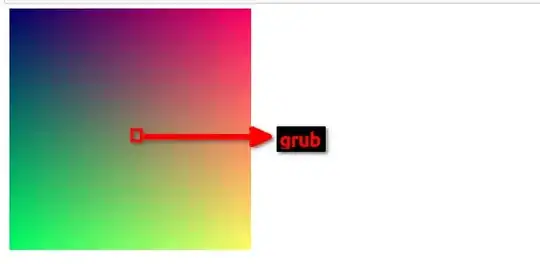

So, first things first, humans and your aliens can both see 550nm, so they can both see something we call "green," and it's possible (theoretically, depends on declination) that they can convince each other they're seeing the same color. They are, so it can't be too terribly hard — and the same is true for the entire shared spectrum of 500nm–740nm.

Where there's a problem is when we point to our own sky and say "blue" and the alien looks up and sees, well... other than glare from the sun, a black sky full of stars. Or when the alien looks at infrared and we see nothing at all.

How humans and your aliens would react to the realization that one can see something the other cannot and vice-versa is storybuilding.

Edit: After reading the comments to my answer and the other answers, I need to add to my answer. Regardless the science-based tag, the only viable answer to the question is, "there's a difference if you want one."

Problem: We've never met an alien.1 All we can work with is the terrestrial life on our own planet. Humans generally see color the same way2 (read the footnote before disagreeing) and only particularly disagree about interpretation when the differences are cultural or in relation to fine shades. But would an alien have any problems?

Before answering that question, let's consider some information I gave in an answer to another question.

But, what color does the animal see? Vision, like all of our senses, is processed in the brain. Without being able to get into the head of an animal, it is only possible to know what colors can be detected and not how they "look" to the animal. (source)

This means that we're making assumptions about the aliens when trying to answer the question. Simplistically, we're assuming that their eyesight and color processing capacities are identical to humans other than the shift in the perceptible spectral range. That could be true... but it also might not be true (and this is the gist of @AlexP's comments, below). We can see an example of this on a terrestrial level where humans have only three color receptors in our eyes, some animals have six, and one butterfly has a whopping 15 color receptors (Source). In other words, we could test such animals (testing the butterfly might be problematic...) to see if they "perceive" color the same way humans do.

What we'll learn, of course, is that they won't because they can see more colors than humans can (especially that butterfly). They'll react to colors we can't see (or, more accurately, can't distinguish). At best we'd learn that they can see a wavelength, but we can't know what that wavelength "means" to them. Yes, we could train them (and probably have) to react a specific way to a wavelength (and that's one way to answer the OP's question) but that's not quite my point.

What is my point? We've all done the best we can to provide science-based answers to a question that lacks the details necessary to be a science-based question. And part of it was falling into the temptation of addressing the "Would this mean that they call 500nm purple?" question, which should have got the question closed for Needing More Focus. But it's also an irrelevant question — the aliens will have their way of identifying colors near the 500nm wavelength just as we do, and given enough time to communicate, the two groups would figure out a way of cross-identifying the name(s) and reaction(s) (both scientific and cultural) assigned to the region around that wavelength. What we all should have been focused on was the last question, which can't be answered until the OP explains at least the basic construct of the alien's eyes and neural processing.

Thus, the answer to the OP's question is, "there's a difference if you want one."

1 <Citation Required>

2 In reality, each and every one of us perceives color differently. The case of color blindness is simply the most obvious and most egregious case. Those of us who have worked with graphic design know that color selection is problematic if you're looking for a specific emotional response because (a) different cultures assign different meanings to color and (b) we all see color differently. However, when it comes to "the perception of color," we all recognize common averages without trouble. Why? Because we all know what a plant leaf is, and the colors of tulips, and the colors of the sky. Therefore, arguments that aliens "could" perceive color differently are frankly specious because humanity has already proven that common interpretations between intelligent (meaning: we can communicate specifically with one another) beings can be created. This is why when you say "green" all English speakers know what you're talking about well enough that the small distinctions (chartreuse? celadon? sage?) rarely matter.

Also, those pretty false-color space images should include a diagram of what receptive field is mapped to R vs G vs B as well as the image's gamma and a summary of how it is filtered.

– Kevin Kostlan Jan 24 '24 at 00:05